Reproducible Notebooks

Millions of Jupyter notebooks are spread over the internet - machine learning, astrophysics,biology, economy, you name it. “What a great age for reproducible science!” - Or that’s what you think until you try to actually run these notebooks. Then you realize that having understandable high-level code alone is not enough to reproduce something on a computer.

Below the superficial charm of a well-written notebook lurks a messy web of low-level dependencies. A notebook doesn’t know how to set those up. Dozens to hundreds of libraries can be called and all of them can potentially influence the final results. Setting them up correctly is painful, requiring a different strategy for each programming language. In a previous post, we used a Docker container to circumvent this problem but a Docker container is difficult to customize. Thus it is often non-trivial to run an arbitrary notebook on a machine different from the one it was written on.

This blog post is about defining and reproducing the compute environments below the surface of a Jupyter notebook. We will show how to setup configurable and reproducible Jupyter environments that include JupyterLab with extensions, the classical notebook, and configurable kernels for various programming languages. These environments are declarative, which means that their content - not the steps required to install them - is defined in a few lines of code. A single command installs and runs the compute environment from the configuration file.

Under the hood, we use the Nix package manager, which enables us to build up such composable environments with simplicity. The Jupyter environments can also be containerized with a single Nix command as a Docker image. Such Docker images can then be served with JupyterHub to give multiple users access to a well-defined reproducible environment. With this setup, installation of a Jupyterlab environment with multiple kernels such as in the following image is easy and robust:

A reproducible compute environment is certainly not the only thing that is required to reproduce a notebook. Just think of a random number generator that could be called in one of the code cells. If the seed is not properly set, the notebook will look differently after each run. Reproducible compute environments are therefore only a necessary first step on the road to full reproducibility.

Declarative Environments

How does such a reproducible compute environment look like?

Here is a simple example.

First, make sure that Nix is installed on your computer. This

works on any Linux and macOS, and won’t modify any files except create

one single directory in your filesystem.

Then, write a shell.nix file with the following contents:

let

jupyter = import (builtins.fetchGit {

url = https://github.com/tweag/jupyterWith;

rev = "10d64ee254050de69d0dc51c9c39fdadf1398c38";

}) {};

ihaskell = jupyter.kernels.iHaskellWith {

name = "haskell";

packages = p: with p; [ hvega formatting ];

};

ipython = jupyter.kernels.iPythonWith {

name = "python";

packages = p: with p; [ numpy ];

};

jupyterEnvironment = jupyter.jupyterlabWith {

kernels = [ ihaskell ipython ];

};

in

jupyterEnvironment.envand run nix-shell --command "jupyter lab".

After downloading and building of all dependencies, this should open a shell and launch JupyterLab.

That’s it, all the kernels are installed, and all libraries are accessible to them.

Although the first run can take quite a while, subsequent runs are instant because all build steps are automatically cached.

More examples of JupyterWith, including Jupyterlab extensions, Docker images, and many other kernels can be found in the README of the project.

Behind the scenes: Nix

Packaging Jupyter with kernels from many different language ecosystems is complicated. Language specific package managers can only handle their own subsystems and often rely on libraries that are provided by the underlying operating system. If one manages to set all of these up together, the outcome will be conflict-prone and difficult to change. This is where the Nix package manager enters the scene.

Nix is a package manager whose packages are written in the Nix language, which can be thought of as a simple configuration language but with functions.

It is used to describe derivations, build recipes that describe every step necessary to build a binary or library from source.

A derivation knows its dependencies, source code locations and hashes, build scripts, environment variables and so on.

Nix is powerful because we can describe derivations programmatically, as we did for example with the jupyterlabWith, iPythonWith and iHaskellWith functions.

We can also programmatically compose different derivations, our own or the ones from the enormous Nixpkgs repository, to generate new ones.

For example, different kernels that are themselves composite packages can be combined with Jupyterlab into a single application.

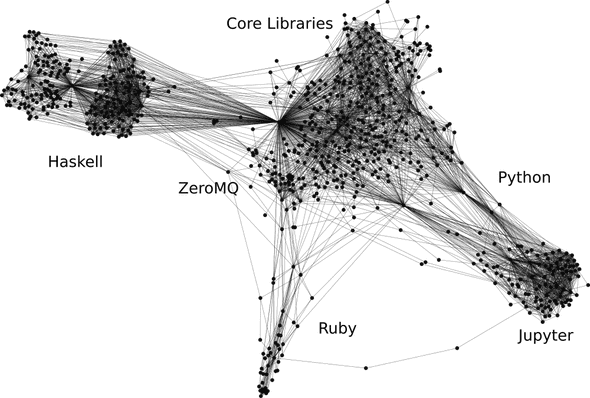

The output is a big dependency web that links the final build output, i.e. Jupyterlab with kernels to all of its dependencies as shown in this dependency graph:

Packages and their dependencies are represented as interconnected nodes in this graph. Such a graph is called the closure of JupyterWith, that is the set of all derivations that are required to run the Jupyterlab. This means that the environment generated by JupyterWith includes not only Jupyter and its kernels, but also all system packages that are required. This guarantees a high degree of reproducibility.

The final JupyterLab environment is complete to a point that we can simply copy it into a base docker Alpine image to run it. No further installation or configuration is required.

Behind the scenes: packaging Jupyterlab

Let’s look in more detail into the packaging process of JupyterLab. A JupyterLab environment is composed of three parts:

- the JupyterLab frontend is essentially a browser application that consists of several bundled Typescript/Javascript core and extension modules;

- the Jupyter server is a Python application that intermediates interactions between kernel compute environments and frontends;

- kernels such as IPython or IHaskell execute code that is send from a frontend such as JupyterLab via the Jupyter server.

The Jupyter server is easy to install with Nix because it is just a set of Python packages that have to be put together. Nix already has a fairly well developed Python ecosystem which can be used for this.

Setting up the kernel environments is a bit more tricky. Kernels are independent executables that require independent package sets and environment variables. As is common in Nix, we wrap the kernel executable into a shell script that locally sets all required environment variables. This wrapper script is then exposed to Jupyter with a kernel spec file. For example, the file for the IHaskell kernel looks as follows:

{

"display_name" = "Haskell";

"language" = "haskell";

"argv" = [

"/path/to/ihaskellShell"

"kernel"

"{connection_file}"

];

"logo64" = "logo-64x64.svg";

}Jupyter is made aware of the location of these files through the JUPYTER_PATH environment variable.

For kernels, all we need to do is building packages and setting environment variables.

Nix handles this wonderfully.

When dealing with Jupyterlab extensions we face a problem since Jupyterlab expects to manage them itself.

Usually, they are installed with the command jupyter labextension install which is a wrapper of the Javascript package manager yarn.

Yarn determines compatible versions for the JupyterLab core modules and the required extension modules together with all their Javascript dependencies.

This resolver step is difficult to reproduce with Nix, since Nix is not about finding compatible versions.

Even worse: it doesn’t even make sense to use the precise versions that yarn determined and feed them into Nix.

Every combination of extensions can have a different set of compatible versions, which means that we can’t pre-resolve all of them.

We therefore pre-build JupyterLab into a custom, self-contained folder with all required extensions.

This folder is the starting point of the Nix derivation and can be referred to from the shell.nix file.

Conclusions

Jupyter is a showcase example for the power of a configuration language like Nix combined with the Nixpkgs collaborative project to describe all open source packages out there. With a few lines of Nix code, we can pull together dependencies from various language ecosystems in a robust way and build configurable compute environments and applications on top of them. Such configurable compute environments can be used and distributed in various ways, including Docker containers. This is a boon for reproducible science: declaratively specify your dependencies and compose your dependency descriptions to incrementally build larger and more complex notebooks that you know will run now and forever in the future.

Suggestions and PRs on JupyterWith are welcome!

Behind the scenes

Matthias initiates and coordinates projects at Tweag. He says he's a generalist "half scientist, half musician, and a third half of other things" but you'll have to ask him what that means exactly! He lives in Paris, and is regularly in Tweag's Paris office where you'll most likely find him in a discussion, writing long-form texts in vim or reading and occasionally writing code.

If you enjoyed this article, you might be interested in joining the Tweag team.